Unnamed Classes and Instance Main Methods (JEP 445)

When people complain that Java is too verbose, they like to point at public static void main(String[] args). That is a pain point when teaching beginning students. I always tell students to just copy/paste without worrying, and I never had anyone complain. But many instructors dutifully explain each syntactical element, and I wouldn’t be surprised if the students’ eyes glaze over. JEP 445 to the rescue. You can pick a version of main that makes sense for your teaching style. And if you teach “objects late”, you can use what looks like global variables and functions. They are actually instance variables and methods of an unnamed class.

Ever since Java 1.0, the entry point for a Java program is a method

public static void main(String[] args)

For teaching Java, this is not wonderful. Why static? Why String[] args? Many years ago, I submitted a patch to the java launcher that allowed it to instantiate any class without a public static void main(String[] args) and with a no-args constructor:

public class MyFirstObject { // My proposal—got nowhere

public MyFirstObject() {

System.out.println("Hello, world! I was just constructed.");

}

}It was rejected for some spurious reason.

As an aside, for some time, it was possible to do something similar (but also not wonderful for teaching):

public class NoMain { // Up to Java 6

static {

System.out.println("Hello, world! Ignore the message below.");

}

}Calling java NoMain would execute the static initializer, followed by an error message about a missing main. This was fixed in Java 7

In Java 8, the java launcher gained special support for launching JavaFX applications without public static void main. But it doesn’t help for teaching the “first cup of Java”.

Finally, Java 21 will support easier ways for writing simpler Java programs. Professional programmers won’t care, but it should lower the barrier to entry for beginning students.

Main Methods

JEP 445 allows, as a preview feature in Java 21, a greater variety of main methods as an entry point of a Java program.

mainneed not bestatic, provided the class has a no-arg constructormainneed not bepublic. It can also have default visibility (no modifier), or be declared asprotected. It cannot beprivate.- The

String[]parameter can be omitted.

That means there are twelve possible forms of main. Here is the shortest version of the classic “Hello, World!” program:

class HelloWorld {

void main() {

System.out.println("Hello, World!");

}

}You can launch a class that has multiple main methods—in fact, up to four, since you cannot overload on visibility. A static main method has preference over an instance method. If that leaves two candidates, the one with a String[] parameter has precedence.

The main method can be declared in a superclass. This has always been true for public static void main(String[]). I don’t see why anyone would do that, though.

As with all preview features, you need to use the --enable-preview flag with the java launcher. For compiling, the flag is not needed because it was always legal to have methods of all kinds called main.

This sandbox shows the four forms of main methods. Rename them to main and re-run the program to see which one is picked by the launcher.

Unnamed Classes

A second feature of JEP 445 allows you to further shorten simple programs. When a source file contains at least one method that is declared outside the class, the compiler will place any such methods inside an unnamed class. The unnamed class also contains any top-level fields. Classes, interfaces, records, and enumerations that are declared in the source file are nested inside the unnamed class.

Since the class is unnamed, it cannot be instantiated programmatically. The only way to instantiate it is to launch it via a main method. It is a compile-time error if there is no such method.

Now our simplest source file becomes:

The class has to have some name, of course. When you place this code into a file SimplestHello.java, the class name is SimplestHello. I think one should consider that an implementation detail and launch such files with JEP 330:

java --enable-preview --source 21 SimplestHello.java

Note that you provide the source file name to the java launcher.

You can have functions other than main:

String greeting(String greeted) {

return "Hello, " + greeted + "!";

}

void main() {

System.out.println(greeting("World"));

}This top-level variable is an instance variable of the unnamed class.

String greeted = "World";

void main() {

System.out.println("Hello, " + greeted + "!");

}The JEP authors explored whether it makes sense to go further and also have an “unnamed method”, similar to the top-level statements in a Python program. However, that is not so simple. Presumably we would still like to support other methods:

String greeting(String greeted) {

return "Hello, " + greeted + "!";

}

// In unnamed function—not part of this JEP

System.out.println(greeting("World"));That would work—we would have an unnamed class with a named method and an unnamed instance method (which only the launcher would call).

But what about variables? For consistency

String greeted = "World";

would have to be an instance variable, accessible in all methods. That’s pretty weird, particularly for variable declarations that come after statements. Therefore, unnamed methods were not pursued at this point.

Another beginner-hostile feature is System.out.println. One has to explain that out is a static variable of System. And it is public final. But why isn’t it System.OUT like other constants? And some student will read the API and ask how a final variable can change with System.setOut.

One could have out implicitly imported (similar to STR in JEP 430), or add a println method to the unnamed class. Should one then do the same for input? System.in isn’t useful enough on its own, so one would need to create a Scanner or Console instance, or at least one reader method. It may make sense to do this in the future.

Objects Early

When I wrote my first college book that used Java as an introductory programming language, I pretty much translated a C++ book. Variables, branches, loops, and then functions, erm, methods. Static methods of course. I didn’t love it. Students had to learn that all methods had to be static, and then unlearn that a few chapters later.

In the next edition, I started out with using objects. Writing simple classes. Then branches, loops, and array lists. Then cycle back to OO design, interfaces, and a light dose of inheritance. This approach is now called “objects early”.

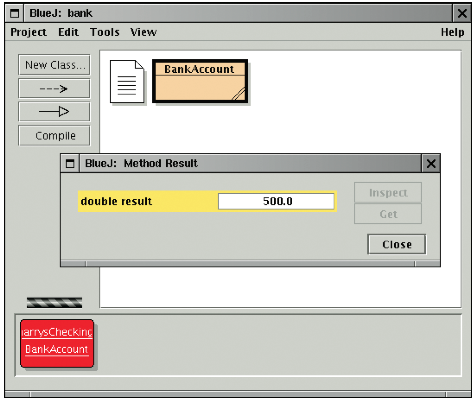

Then public static void main is particularly unappealing. In fact, I use the excellent BlueJ environment in which you can instantiate classes and call methods without ever calling main. I highly recommend it for a beginning course.

JEP 445 will help out. I can simply replace public static void main(String[] args) with public void main(), and I am done. I don’t need the unnamed class, and won’t mention it.

I could consider dropping public and private modifiers, but they don’t really bother me. They make it easy to explain encapsulation. Students seem to have no trouble with a rule “methods are (mostly) public, instance variables private”. And if they accidentally omit the modifiers, I don’t make a big deal out of it.

My one issue is the name of the method. We teach students that class names should be nouns and methods verbs. Like Greeter and…well, not main. I’d be happier with something like run. But I can see the wisdom of just expanding the existing main launch mechanism.

Objects Late

Not everyone is comfortable with objects early. If one brings out too much OO machinery in the first few weeks, students can be overwhelmed. The traditional approach, with variables, branches, loops, functions (erm, methods), arrays, and then classes, is often called “objects late”.

That approach becomes a lot smoother with JEP 445. You start with the unnamed class and put statements into void main(). Then you add more instance methods. Hooray, no more static. Then you introduce classes and confess that students have used a class with no name and a single instance all along.

Admittedly, it would be even easier if one didn’t have to introduce main on day 1, but we’ve lived with main when teaching C++, and nobody complained.

Will this be a revolution that makes teachers reconsider their foolish move to Python? I am afraid not. The real advantage of Python for teaching is not that “Hello, World!” is a one-liner. With Python, it is easy to design projects that students find interesting. In the heyday of Java in education, an interesting project had a GUI and a database, and connected to the Internet. Just the sweet spot for turn-of-the-millennium Java. To do the same thing in C++ or Python would have been a true pain. But nowadays, interesting projects involve data science and machine learning. And those are a pain in Java. There is no Java notebook that makes it easy way to grab, manipulate, and plot data. There are Java bindings to ML libraries, but it’s a lot more work to put together a lab or assignment than it would be with Python, where the internet is replete with easy-to-clone projects.

Conclusion

- When introducing Java for the first time, you almost certainly don’t want to talk about

static. OrString[] args. Now you can usepublic void main()or, if you don’t yet want to mention modifiers,void main(). - In an “objects late” curriculum, you don’t even need a

public classwrapper. Just providemain(), functions that are called frommain(), and global variables. Eventually, introduce classes and reveal to students that these are instance methods and instance variables.