Sealed Types (JEP 409)

Java 17 provides “sealed types”—types with a fixed set of direct subtypes. This feature allows for accurate modeling of type hierarchies that should not be open to arbitrary inheritance, and it allows the compiler to check for exhaustive pattern matching.

Controlling Subtypes

Unless a class is declared final, anyone can form a subclass of it. What if you want to have more control? For example, suppose you feel the need to write your own JSON library because none of the ones out there do exactly what you need.

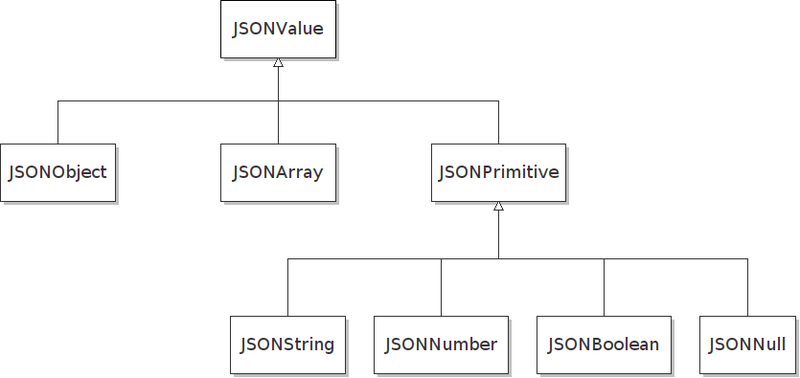

The JSON standard says that a JSON value is an object, array, string, number, Boolean value, or null. The Java language had, until now, no way of expressing that a JSONValue should be exactly one of those six types.

Java 15 provides a preview of “sealed types”, where you get just that control. You can define JSONValue to be sealed, and list the subclasses in a permits clause:

public sealed abstract class JSONValue

permits JSONObject, JSONArray, JSONString, JSONNumber, JSONBoolean, JSONNull {

. . .

}If anyone were to form another subclass, such as

public class JSONComment extends JSONValue { . . . } // Errorthis would be an error. And that’s just as well, since JSON doesn’t allow for comments. As you can see, sealed classes allow for accurate modeling of domain constraints.

The dictionary defines sealing as (1) affixing a mark that attests to quality or absence of tampering, or (2) securing against access or damage. I am not sure that either of these describes what the sealed keyword does. A sealed class is protected from one specific evil, namely promiscuous subclassing.

Exhaustiveness

Sealed classes enable the compiler to reason about exhaustiveness. For example, in the following function, it would be possible for the compiler to conclude that no further return is needed:

public static String type(JSONValue value) {

if (value == null) throw new NullPointerException();

else if (value instanceof JSONObject) return "object";

else if (value instanceof JSONArray) return "array";

else if (value instanceof JSONString) return "string";

else if (value instanceof JSONNumber) return "number";

else if (value instanceof JSONBoolean) return "boolean";

else if (value instanceof JSONNull) return "null";

}Actually, Java 17 does not carry out that analysis for if statements, but it does so for type patterns in switch expressions (which are a preview feature in Java 17).

Subclasses Must Specify Their Sealedness

At first glance, it appears as if a subclass of a sealed class must be final. But for exhaustiveness testing, we only need to know all direct subclasses. It is not a problem if those classes have further subclasses. For example, we can reorganize our JSON hierarchies like this:

Then the sealed JSONValue class permits three subclasses:

public sealed class JSONValue permits JSONObject, JSONArray, JSONPrimitive {

. . .

}What about JSONPrimitive? It should be a sealed class in its own right:

public sealed class JSONPrimitive extends JSONValue

permits JSONString, JSONNumber, JSONBoolean, JSONNull {

. . .

}The other classes should be final.

public final class JSONObject extends JSONValue { . . . }A subclass of a sealed class must specify whether it is sealed, final, or open for subclassing. In the latter case, it must be declared as non-sealed.

As an example, consider XML node types: elements, text, comments, CDATA sections, entity references, and processing instructions.

sealed class Node permits Element, Text, Comment,

CDATASection, EntityReference, ProcessingInstruction {

. . .

}We might want to allow arbitrary subclasses of Element (as does with org.w3c.dom.Element, which has dozens of HTML element subclasses). Then the declaration goes like this:

non-sealed class Element extends Node {

. . .

}New Keywords and Restricted Identifiers

The tokens sealed and permits are restricted identifiers that have a special meaning only in class and interface declarations, just like record, var, and yield. Code with variables named sealed and permits won’t break. But you can no longer define classes named sealed and permits:

In contrast, non-sealed is a keyword. Obviously, you cannot use it as an identifier since it contains a - character. In fact, non-sealed is the second keyword that contains a character that isn’t a lowercase letter. The first one is _, since Java 9.

And yes, you can continue to compute the difference of two variables non and sealed:

Package/Module Restriction

If you don’t use modules, then the sealed class and its direct subclasses must be in the same package. If you use modules, they must all be in the same module.

After all, these classes are developed and maintained together, so there should be no reason to spread them far and wide.

There is one vexing situation. If you don’t want to use modules, you cannot put the superclass into an API package and the subclasses into a separate implementation package.

Omitting the Permits Clause

If the subclasses of a sealed class are all defined in the same source file, then you can omit the permits clause:

Then the permitted subclasses are all direct subclasses of the sealed class in the same source file. If you want the subclasses to be public, they must be nested classes, as in the example above.

If you omit the permits clause and there are no direct subclasses in the same source file, a compile-time error occurs.

Sealed Interfaces

An interface can be sealed just like a class. It has a fixed set of permitted direct subtypes.

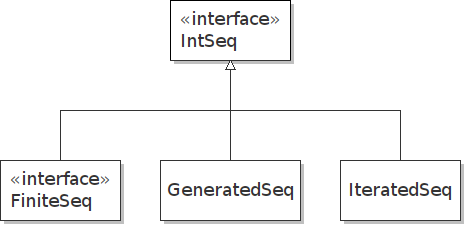

Here is an example. An integer sequence produces one integer after another, potentially infinitely many:

public sealed interface IntSeq permits FiniteSeq, IteratedSeq, GeneratedSeq {

int next();

default boolean hasNext() { return true; }

}There may be any number of ways of implementing finite sequences, and we aren’t prescriptive:

public non-sealed interface FiniteSeq extends IntSeq {

int size();

}But for infinite sequences, we only support two implementations: with a generator function or an iterator function—similar to Stream.generate and Stream.iterate.

As you can see, with a sealed interface, the situation is a bit more complex. Its direct subtypes can be both interfaces and classes. But the rules are the same. All direct subtypes must be listed in the permits clause, or be in the same source file. And they must all be final, sealed, or non-sealed.

Sandbox with complete code:

Records and Enums

A sealed interface can be implemented by a record, which is implicitly final. Consider the classic example of a Lisp-style list:

public sealed interface IntLst {

record NonEmpty(int head, IntLst tail) implements IntLst {}

record Empty() implements IntLst {}

static IntLst cons(int head, IntLst tail) { return new NonEmpty(head, tail); }

static IntLst empty() { return new Empty(); }

}If the list is non-empty, it has an initial value, the head. And a tail—the list with all other values. Otherwise it is empty.

We use two record types to implements each of these possibilities.

To analyze such a list, use recursion. If the list isn’t empty, the sum of the elements is the head + the sum of the tail. Otherwise the sum is zero:

public static int sum(IntLst lst) {

return (lst instanceof IntLst.NonEmpty ne) ?

ne.head() + sum(ne.tail()) : 0;

}It is a bit wasteful to construct a separate instance of an Empty at the end of every list. We could have a single object for all empty lists. An excellent way to get a single instance is with an enumerations. An enumeration can extend an interface. Therefore it can appear as a permitted subtype of a sealed interface:

Generics

Sealed types and their direct subtypes can be generic. Just to show that it can be done, here is a generic Lisp-style list. As usual, some generic machinations look a bit forbidding, but it works without surprises.

Reflection

Two methods have been added to java.lang.Class to support sealed classes. The method isSealed returns true for a sealed class.

The getPermittedSubclasses method returns an array of Class objects describing the permitted subclasses. (For Class objects that don’t describe sealed classes, the result is null.)

Summary

Sealed types are fairly straightforward. Here are the key points to remember:

- A sealed type has a fixed set of direct subtypes

- The direct subtypes of a sealed type must be listed in a

permitsclause, or, if there is no such clause, be in the same source file. - The direct subtypes of a sealed type must be

final,sealed, ornon-sealed. - Future pattern matching features can carry out exhaustiveness checking with sealed types